How Sam Altman Chose Influence Over Billions (And Got Both)

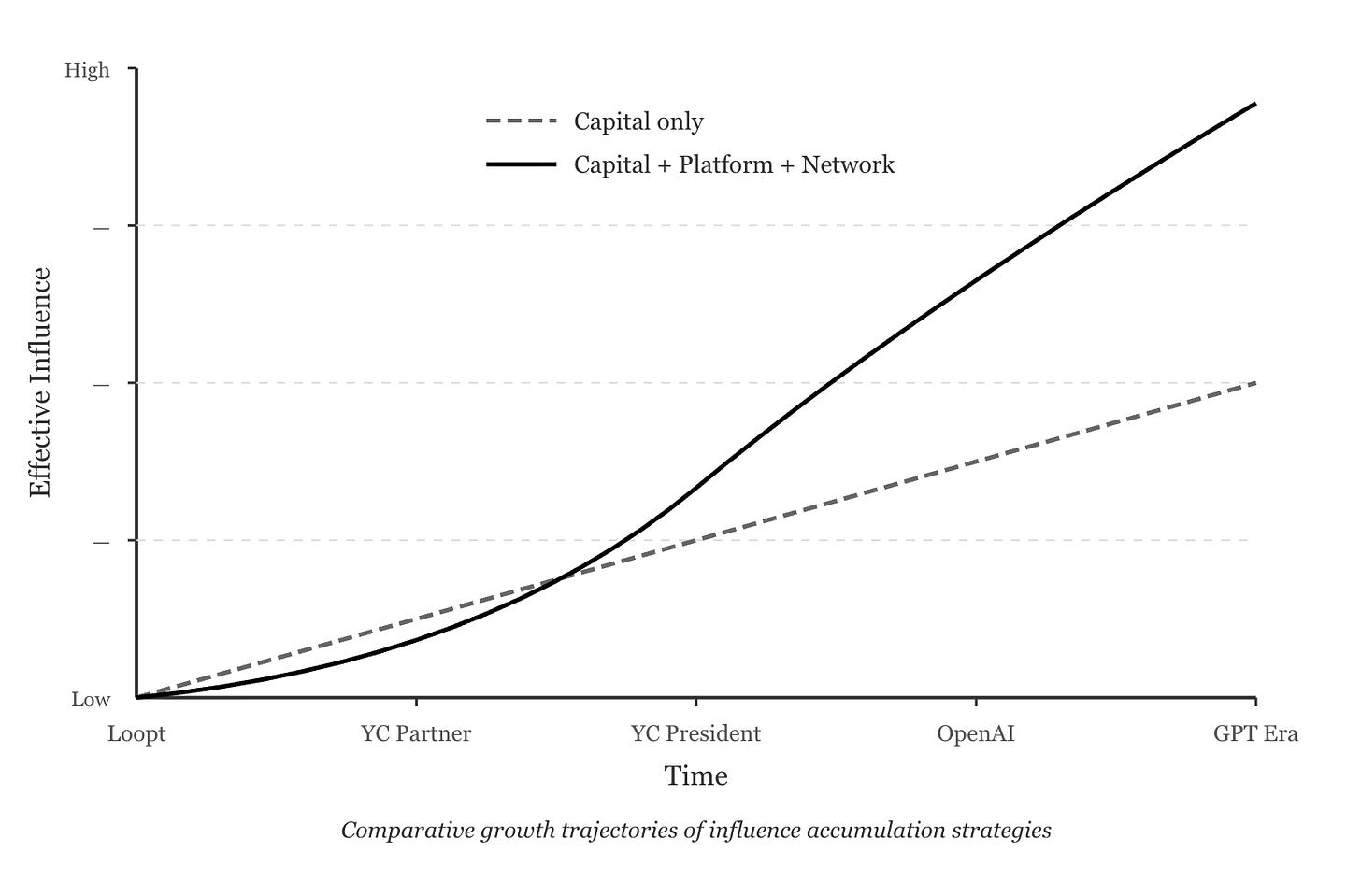

Influence compounds differently than capital.

Sam Altman is unusually good at attracting suspicion.

Depending on who you ask, he’s a visionary trying to steer an unstable technology, or a power-maximizer using “AI safety” as cover. Every news cycle produces a new round of cynical takes: too polished, too political, too eager to sit at the center of the system.

What almost none of those takes do is treat him as a deliberate strategist over a 15-year arc.

Because there is a concrete, traceable story here: how a twenty-something with a decent-but-not-spectacular exit moved laterally, again and again, into roles that controlled distribution, capital, and eventually an entire AI super-cycle.

Whether your feelings are admiration or not, you don’t have to approve of the outcome to learn from the method. And you should.

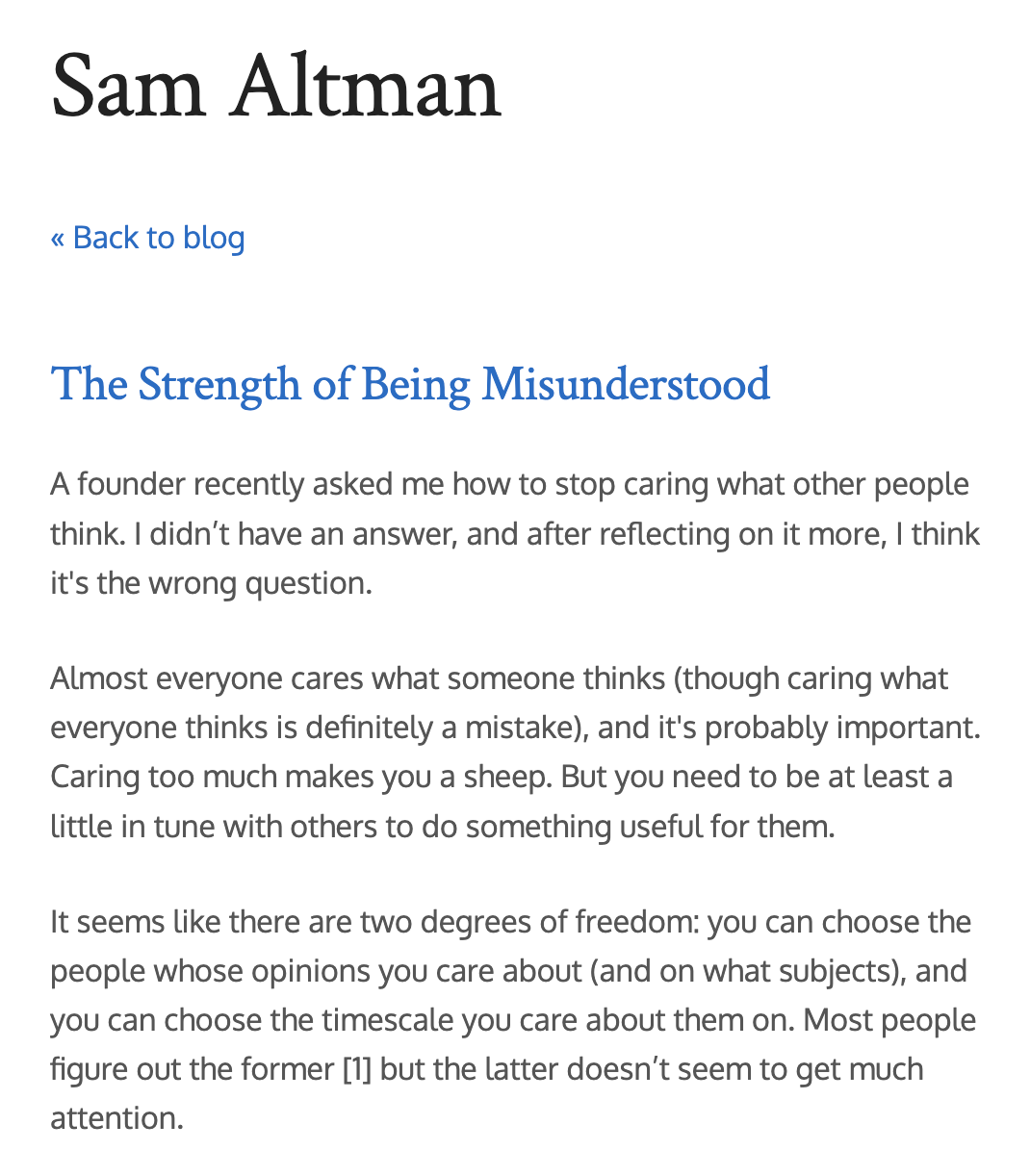

Altman has, helpfully, left a paper trail. In 2020, in an essay titled The Strength of Being Misunderstood, he argued that the question isn’t “How do I stop caring what people think?” It’s “Whose opinions should I care about and on what timescale?”

Most people, he wrote, figure out the first but neglect the second.

He says the most impressive people he knows care deeply about what others think, but on a very long horizon. They’re willing to let “the newspapers get it wrong” so long as “the history books get it right.”

That frame explains quite a lot about the career that followed.

Why Combinator?

In March 2019, Altman faced a very binary choice.

For a little over three years, he’d been running two organizations at once:

Y-Combinator, where he’d become president in 2014, gave him access to over a hundred startups per batch and hundreds per year.

OpenAI, which he’d co-founded in 2015, was still mostly a research lab, even as it became more than an academic exercise.

YC’s leadership told him he had to pick one: commit full-time to YC or commit full-time to OpenAI.

He chose OpenAI.

To most people in tech, this looked insane. “President of YC” was the most powerful position in startup land. Direct access to hundreds of companies per year, the ability to shape an entire generation of founders, and a platform that had minted some of the most valuable companies of the decade.

He walked away from it for an odd hybrid: a nonprofit-controlled, “capped-profit” AI lab that still looked more like a research shop than a product company.

Even if it managed to raise serious capital, it was still fundamentally competing with DeepMind, Google Brain, and FAIR on research.

The conventional wisdom was clear: you don’t give up the top of the mountain to bet everything on a weird research lab.

Altman bet on it anyway.

Choosing Platforms Over Exits

The standard path to influence in Silicon Valley is simple enough: get into a rocketship early, ride it to a huge exit, and let the combination of wealth and “I was there” carry you into every important room.

Altman’s path diverged from that script early.

He co-founded Loopt in 2005, went through YC himself, and spent years grinding on a location-based social app that never quite hit escape velocity. In 2011, while still running Loopt, he joined Y Combinator as a part-time partner.

Loopt was sold in an acqui-hire for about $43.4 million in March 2012. With dilution, terms, and the like, his take-home was likely around $4-6 million. Life-changing money, but not “you now own a large fraction of the internet” money.

At that point, the obvious move would have been: do it again. Start another company, knowing more and having more.

He didn’t do that. He used part of the Loopt proceeds to launch Hydrazine Capital, an early-stage fund focused heavily on YC companies. He bought himself a position slightly up the stack, allocating capital across many bets instead of concentrating everything on one.

Then in February 2014, at 28, Paul Graham asked him to become president of YC.

This wasn’t a difficult decision. This was Paul Graham handing him the most powerful platform in startup land. Of course you say yes. Direct access to hundreds of founders per year, the ability to shape how an entire generation thinks about building companies, and a reputation-compounding machine that had already minted Airbnb, Dropbox, and Stripe.

What was unconventional wasn’t taking the role. It was how he used it.

Most people would have treated YC as a job. A prestigious job, but still: show up, run the batches, give advice, post on Twitter, collect the salary and carry. Altman treated it as infrastructure for something else.

You can already see the pattern forming:

Trade operator role in one company for a platform role across many companies

Trade clean ownership for messy, leveraged influence

Trade near-term clarity for long-term optionality

That pattern repeats.

The Multiplier

Altman’s core ethos is simple:

Influence compounds differently than capital.

Capital compounds through returns on financial assets. Influence compounds through network effects.

With money, you can put dollars into deals and hope to get more dollars out. With access and a platform, every interaction is a potential edge: introductions, information flow.

YC was a perfect laboratory for this.

Every batch, Altman met dozens of founders at the most malleable stage of their careers. He saw everything: the raw deck, the dysfunctional founding teams, the early flashes of product-market fit. He had leverage over what they built, who they met, and how they thought about ambition and risk.

A lot of those companies disappeared. But some became Instacart, DoorDash, and Coinbase. Their founders were the ones who remembered who took them seriously when they were pitching half-finished slides to a conference room on Pioneer Way.

Notice the selectivity. Altman didn’t help everyone. He helped people who were ambitious, building something, playing a long game. People who might be important later.

This created a particular kind of reputation. People don’t say, “Sam helped me because he calculated I’d be useful to him later.” They say, “Sam helped me when no one else would.” Both things are true. The calculation doesn’t diminish the value of the help.

From the outside, this looks like “being generous with your time,” as Bay Area figures often are.

From the inside, it’s a very specific kind of leverage:

Each founder you help is a future allocator of equity, attention, and introductions

Each company that works becomes a node in your personal distribution network

Each batch increases both the number of nodes and the density of edges between them

Most people treat “networking” as a set of social obligations. Altman treated YC as a compounding system.

Strategic Opacity

How comfortable Altman is being misread in the short term matters as much as any specific bet he’s made.

In The Strength of Being Misunderstood, Altman argues you should be very selective about whose opinions you weight and on which topics, and that you should care about those opinions on a very long timescale. You should be willing to trade “short-term low status” for “long-term high status,” which means being patient about looking foolish or wrong.

Once you read that, his public behavior looks less enigmatic.

Altman will talk at length about AGI timelines, universal basic income, or the need for more energy. He’ll lay out his views on what a healthy tech ecosystem looks like. But when it comes to concrete maneuvers (why he backed a particular structure, what exactly he promised which investor, what line he’s walking with regulators), the record gets much thinner.

That isn’t an accident. It’s a division of labor:

Worldview: broadcast widely; invite allies; build consensus over decades

Tactics: keep quiet; let results, not blog posts, explain the moves

This creates something valuable: interpretive room. When Altman makes a move, different people can read different motives into it.

When the OpenAI board ousted him in November 2023, he didn’t immediately go public with a detailed counter-narrative. He let employees, Microsoft, and other stakeholders make the case.

This allowed multiple versions of the story to coexist, each one serving his interests with different audiences.

His public statements on AI safety follow the same pattern. He expresses enough concern to be taken seriously by safety-focused researchers, but remains optimistic enough to keep building aggressively. Both AI accelerationists and AI safety advocates can find something in his public position to work with.

Compare this to someone like Elon Musk, who over-explains as a rule. Musk will tell you exactly what he thinks about everything, in real-time, often emotionally. This creates clarity but eliminates optionality.

You always know where Musk stands, which means you can predict him, oppose him, or potentially box him in. Altman doesn’t give you that opening.

Lesson: Be open about your worldview and frameworks. Be silent about your tactics and specific calculations. Maximum influence, maximum flexibility.

Public Vision, Private Tactics

A big part of why Altman gets read as “calculating” is that he does something most powerful people avoid: he writes down his worldview.

Starting around 2014, his essays began to cluster around a few consistent themes:

Intelligence as the master lever on the future (the 2015 “machine intelligence” posts)

The need for a social backstop like basic income in a highly automated economy (2016 YC basic income project)

Cheap, abundant energy as a foundation for growth (2015 “Energy”)

A belief that we can and should drive the cost of many essentials down over time (”Moore’s Law for Everything”)

By the time he co-founded OpenAI in December 2015, he had already spent reputational capital on the argument that machine intelligence would be both enormously valuable and potentially dangerous.

This matters for two reasons.

First, it makes his later moves legible to long-term observers. When he pivots from running YC to running OpenAI, it doesn’t look like a random lurch; it looks like the obvious next move for someone who has been talking about AGI and social risk for years.

Second, it increases the surface area of his influence. Every essay is an invitation to a different set of people (researchers, regulators, founders, policy thinkers) to plug into his frame for what matters. The result is a much thicker web of people whose default assumption is “Sam is basically serious about this.”

Critics argue about how sincerely any of this is held. But the mechanism is straightforward: public worldview, private tactics. The former earns him trust and attention; the latter preserves flexibility.

The OpenAI Coup

The OpenAI pivot in 2019 is a textbook application of the method.

In December 2015, while still president of YC, Altman co-founded OpenAI with Elon Musk and others as a nonprofit lab. He was operationally involved from day one: fundraising, strategy, recruiting. For a little over three years, he effectively ran both YC and OpenAI.

Then, in March 2019, he made the high-variance move.

OpenAI created OpenAI LP, a nonprofit-controlled “capped-profit” entity designed to raise serious capital while nominally preserving its charter. Altman became CEO of this new structure. A few months later, in July 2019, OpenAI announced a $1 billion partnership with Microsoft and committed to using Azure as its exclusive cloud platform.

What Altman saw that others didn’t:

He saw that AI was going to be genuinely transformative, not in a vague futurist sense but in a three-to-five-year sense.

He saw that the path to influence in AI wasn’t through gradual academic research but through building something people could touch.

He saw that being early to this transition would matter more than being right about any particular technical bet.

The transformation of OpenAI from pure research lab to product company (ChatGPT in November 2022, GPT-4 in March 2023, the expanded Microsoft partnership in January 2023) were Altman moves. They were pragmatic, commercial, and slightly norm-violating. They made OpenAI matter in a way that pure research never could.

The November 2023 board fight (brief ouster, rapid return) revealed how strong the network around him had become.

Hundreds of employees threatened to walk. Microsoft made it clear that the partnership was with Altman as much as with the corporate shell. The board surrendered quickly.

The network he’d built was strong enough that the company couldn’t function without him.

The Method, Distilled

If you just want to understand the mechanics, the Altman method looks roughly like this:

Choose leverage over ownership. Repeatedly trade clean founder equity for platform roles that sit on top of many companies (YC) or entire technology layers (OpenAI).

Design for network effects. Put yourself where flows converge (deal flow, talent, research, distribution) rather than where one product lives or dies.

Invest in selective generosity. Spend time and capital on people who are clearly ambitious and long-term oriented. Think of every introduction, every early check, as a possible future edge in the graph.

Broadcast worldview; hide tactics. Use essays and public talks to explain what you’re trying to do in broad strokes. Say very little about how you’re actually going to do it.

Accept being misunderstood on a long horizon. Be willing to look opportunistic, over-optimistic, or even hypocritical in the short run if you believe the long-run bet is sound. Trade “short-term low status” for “long-term high status.”

Compound patiently. Don’t expect the payoff in a year or even five. Altman co-founded OpenAI in 2015 and didn’t go all-in until 2019. The real returns (ChatGPT, GPT-4, the board fight) didn’t show up until the early 2020s.

None of these moves is spectacular on its own. Being a part-time YC partner, starting a small fund, co-founding a research nonprofit, stepping into a strange “capped-profit” structure: each step is legible but not obviously world-historical.

What makes the story interesting is the consistency. Over fifteen years, Altman has repeatedly optimized for position over immediate payout, for platform over product, for history books over newspapers.

Most people in tech, when they have a modest win, try to roll it into a bigger version of the same game. Altman switched games. He chose to play for influence first and money second.

He ended up with both.

Influence is upstream of capital. Amazing read.

Less enigmatic than strategic. Loved this read.