Why Anthropic Wants to Pay Writers $300,000/Year

They're not paying for words. They're paying for influence.

Note for newsletter recipients: I changed my newsletter’s name from LinkedUp to Sam’s Newsletter to give me room for broader topical coverage in line with how my positioning is evolving (more on that here).

It’s interesting how quickly things change. Three years ago (can you believe it!), when ChatGPT launched, the consensus was obvious: writers were doomed. AI could already write better than most people, and it was only going to get better. If you made your living producing text, you were in trouble.

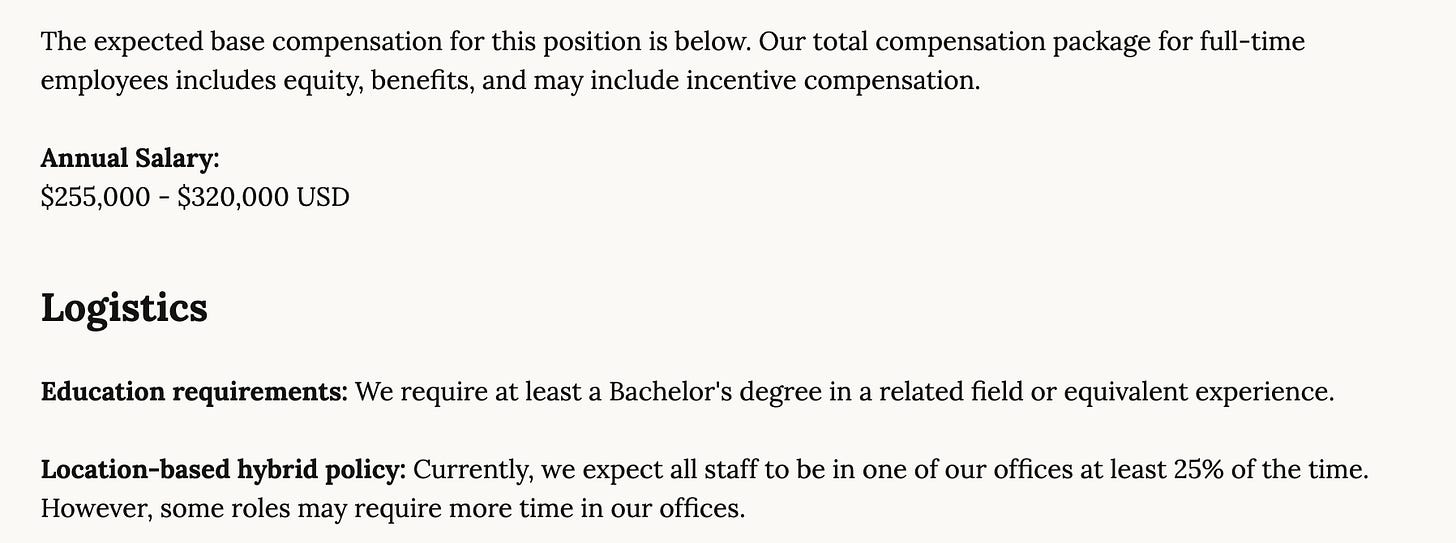

Last week, Anthropic posted a job listing for a writer. The salary range: $255,000 to $320,000.

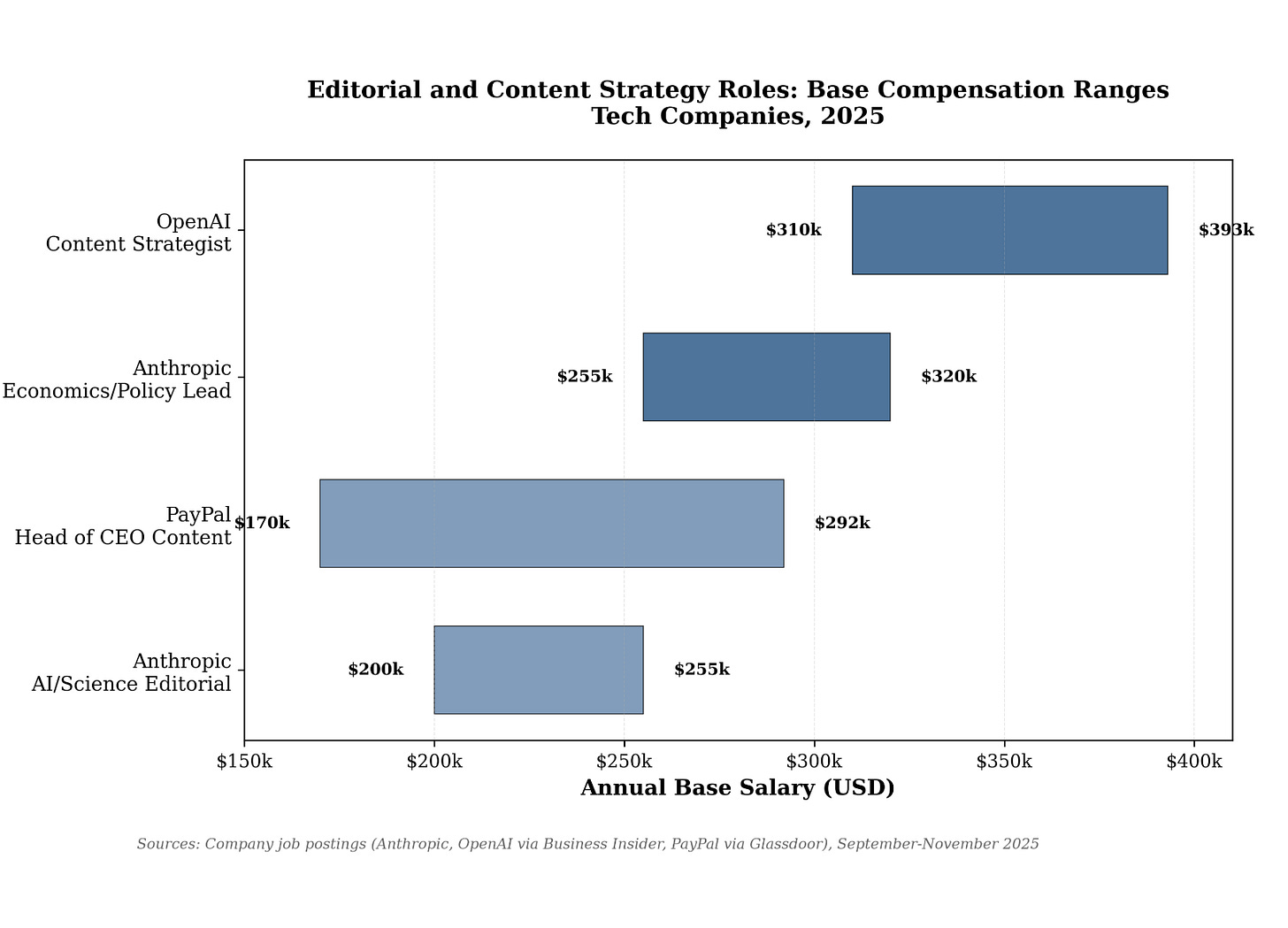

This isn’t Anthropic being quirky. In September, OpenAI posted a content strategist role at $310,000 to $393,000. Same month, PayPal posted a “Head of CEO Content” position with a range cited between $170,000 and $292,000. Just last week, Andreessen Horowitz announced an entire fellowship program for what they called “highly functional people who are also very online.”

I tweeted about the Anthropic JD without thinking much: “Basically all bad/okay writers are near worthless now. Now extremely good writers with great taste trade at a huge premium and own the future of content.”

It got 32,100 views. Which tells you something: people felt this even if they couldn’t articulate it.

Why? Why would Anthropic (the company that makes Claude, probably the best creative writing AI in the world) pay someone $320,000 to write? The obvious answer is they need economics expertise. But The Economist doesn’t pay anywhere near this much. Something else is happening.

Shaping Questions, Not Answering Them

I pulled both of Anthropic’s editorial job postings to see what they actually wanted, and the language is revealing in a way I (mostly) didn’t expect.

The Economics & Policy Lead says:

“Anthropic is at the center of critical conversations about AI’s economic and societal implications.”

Interesting. Continuing:

“[The role will] engage with policymakers, think tanks, academic institutions, and media to advance productive conversations about AI policy and economics.”

Not report on conversations. Advance them.

They want someone with “strong instincts for identifying which policy and economic questions will matter most as AI develops” who can “represent Anthropic’s perspective effectively while engaging constructively with diverse viewpoints.”

Read that first part again. Instead of hiring someone to explain what happened, they’re hiring someone to shape what questions get asked in the first place.

Notice something else: Anthropic posted two editorial roles. The other is for AI and Science, at $200,000 to $255,000. Still substantial, but the policy role pays $65,000 more at the top end. That spread tells you what they think is strategically important.

Algorithmic Negotiation

What these companies are paying for is what I’d call “algorithmic negotiation” at institutional scale. Here’s what I mean by that:

Modern discourse operates on two opposing forces. On one side: the specific knowledge that makes someone worth listening to. On the other side: legibility to the right audiences. Understanding how ideas move through institutions, how frames shift, how to make concepts matter.

Most people can do one or the other. Academics produce rigorous but often unreadable work. PR people produce polished but often empty messaging. The valuable skill is negotiating between these forces without capitulating fully to either.

This requires being embedded in discourse. Not watching it, but living in it. Understanding moves and counter-moves. Knowing which frames are played out and which are fresh. Having what Anthropic’s posting calls “strong instincts for identifying which policy and economic questions will matter most.”

More than simple writing ability, that’s predictive judgment about which conversations determine everything else.

AI can produce clean text explaining any position. But it can’t tell you which position to take, or which question to elevate, or how to shift what the institutions that matter think is important.

What used to be a personal skill is now being systematized.

From Skill to Infrastructure

The a16z fellowship makes this systematization explicit, and it’s where the large strategy becomes clear.

How a16z describes what they’re building: “Forward deployed New Media, where team members embed themselves in portfolio companies for critical periods, and execute a launch together.”

In other words, embed and execute - using the term “forward deployed,” a term popularized by Palantir to describe the concept of sending their engineers into literal warzones to deploy their software for government clients.

The eight-week fellowship has a founding cohort that includes James Reina, Chief of Staff to Mr. Beast. Mr. Beast has 450 million subscribers and routinely gets over 100 million views per video. Reina was inside that operation, understanding how it works.

What is a16z doing here exactly? Extracting operational knowledge about how to build massive audiences, then deploying it strategically.

The speaker lineup includes Marc Andreessen and Katherine Boyle (who both spend lots of time online, specifically on X), Lulu Cheng Meservey (who is famous inside the Bay for flipping the script on PR, guiding clients like Sam Altman and Palmer Luckey out of tricky situations), and Dylan Patel from SemiAnalysis (who turned semiconductor analysis into one of tech’s most influential newsletters).

The fellowship page is explicit about placement: “Potential forward deployment to drive impact at an a16z portco.” They’re embedding them directly into portfolio companies to 10x their influence.

A16z calls this “timeline takeover” - they explicitly offer to “win the internet for a day” as a service.

Their goal, in their own words, is building “the best turnkey media operation in venture” to help founders “win the narrative battle online.” The old agency timeline of three to six months to plan a launch is “archaic,” they write; you now must execute “in a shockingly short period of time.”

What a16z is creating is, ultimately, a pipeline that turns narrative understanding into a competitive advantage for their entire portfolio. They describe themselves as “the F1 Pit Crew of Venture” - systematic infrastructure designed for speed and precision.

Cultural Upstream

This explains something that otherwise seems strange: why do mega-successful entrepreneurs who should be far too busy to post spend hours online?

Elon Musk runs multiple companies. Marc Andreessen runs a major VC firm. Both spend enormous amounts of time posting on X. That looks like distraction until you understand what they’re actually doing:

Building infrastructure to control cultural upstream.

Every industry now has a cultural upstream, and it lives on platforms. In tech, it’s largely Twitter/X. In beauty, it’s TikTok and Instagram. In gaming, Twitch and Discord. The specific platform varies, but the principle is constant.

This creates a recursive loop. The platforms don’t just reflect what’s important. They determine what becomes important. Control the upstream and you control what flows downstream.

From Chaos to System

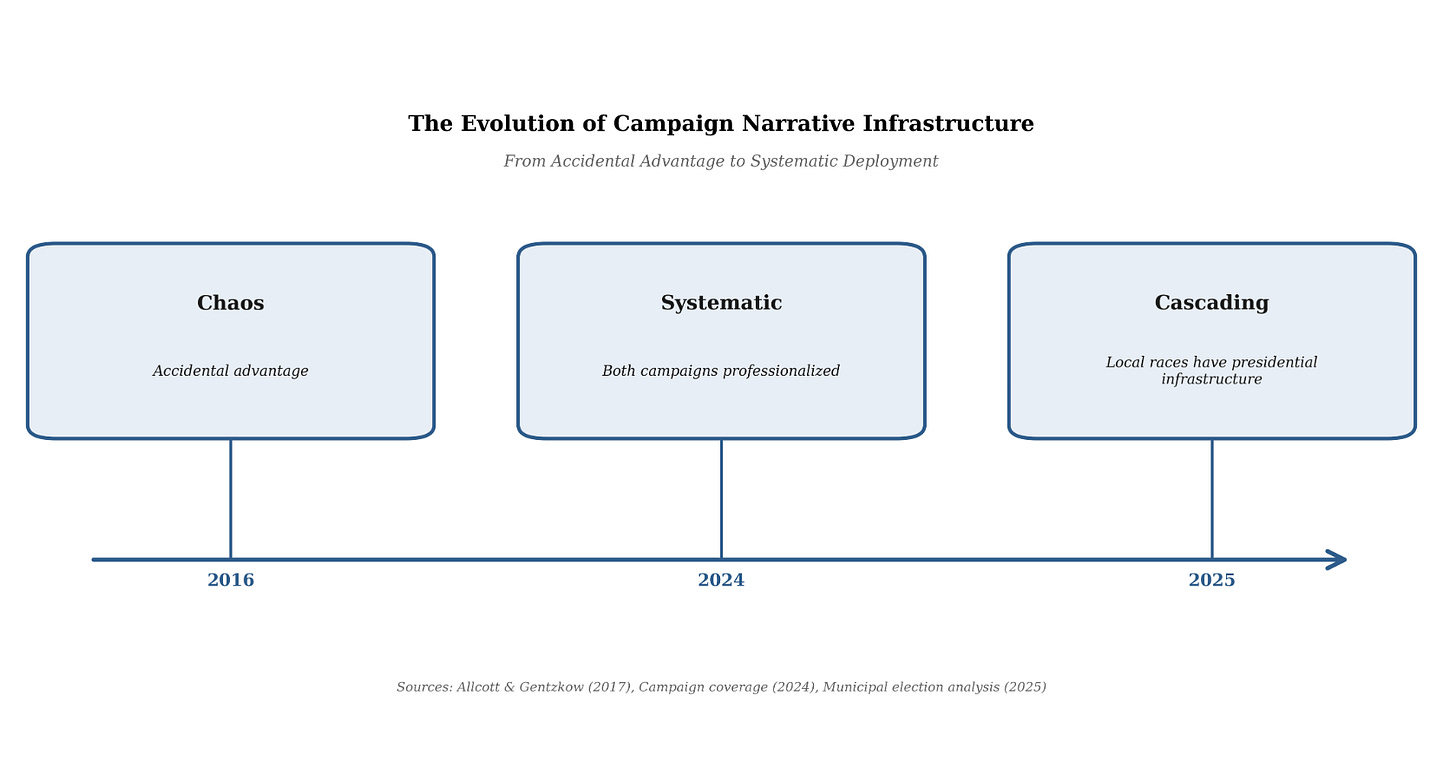

This shift from individual skill to systematic infrastructure isn’t limited to business. In fact, you see it more clearly in politics.

The 2016 election was the first fully social-media-driven U.S. presidential cycle. The outsider candidate won partly because he understood platform mechanics better than his opponent. But it was still somewhat chaotic; his advantage was partly accidental. Wired wrote at the time about how Facebook and Twitter propelled his campaign in ways that hadn’t been systematically planned.

By 2024, everything had changed. Both campaigns were running sophisticated narrative operations. Politico covered how one campaign joined TikTok despite previously trying to ban it - recognizing the platform had become essential to owning the narrative. The Washington Post documented the rapid-response content operations running in real time. GMF called it “the TikTok era” for presidential campaigns. The professionalization was complete at the national level.

This capability is now cascading to local races. What presidential campaigns had in 2016, city candidates have in 2025 (looking at New York City’s mayoral election earlier this month).

Where Power Flows Now

Big picture, I think we’re watching a major reallocation of power.

For most of history, cultural production was controlled by institutions with distribution: newspapers, publishers, TV networks. The internet disrupted that, but for a while, the new equilibrium wasn’t clear.

Now it’s becoming clear. Cultural production happens on platforms, but control requires systematic infrastructure. And not just using the platforms, but building organizational capacity around them.

That’s why Anthropic is paying $320,000 for someone who can be “at the center of critical conversations.” Why a16z is recruiting from Mr. Beast’s operation and forward-deploying fellows into portfolio companies. Why OpenAI is paying nearly $400,000. Why billionaires who should be too busy are spending hours crafting posts for their growing audiences.

They’re building infrastructure for a new kind of power: the power to shape which questions get asked, which frames become standard, what people think matters.

You might find this uncomfortable. We’re watching influence centralize around systematic infrastructure in a way that feels different from what the early internet promised.

Elite institutions are building machinery to occupy the highest levels of cultural upstream, and they’re doing it by hiring the best people at algorithmic negotiation and embedding them (shameless plug: people like me).

But uncomfortable or not, it’s happening. a16z has the language right there on their site: “embed themselves in portfolio companies” for the purpose of pushing their narrative effectively. Anthropic is explicit that they want to be “at the center of critical conversations.”

The bad writers are finished. The okay writers are finished. The content mills are definitely finished.

The people who can identify which questions will matter before they’re obvious, who can engage with institutions while maintaining strategic clarity, who can negotiate with algorithms while maintaining substantive knowledge?

They’re going to own discourse.

And in a world where narrative increasingly shapes reality (where questions determine policies, regulations, and who gets to build) owning discourse means owning outcomes.

The $300,000 salary isn’t for writing.

It’s for power.

And institutions are paying accordingly.

This is the right diagnosis, but I think it’s even cleaner.

They’re not paying for influence or writing. They’re paying to stabilize the question-space before institutions lock in.

Once questions harden, outcomes are mostly predetermined. Writing is just the visible surface of a deeper coordination role.

Copying from LinkedIn: Wow! This is about advancing thought leadership at scale. LLMs operate based on probabilities, so if you feed it all the content of the Internet, especially with the Internet getting more than 50% occupied by AI-written content, what gets amplified will be banal and average. Doing this will ensure that instead, Claude is about propagating top scientific and economic thought to everybody. Master move and thank you Sam for sharing!